A firm seeking to go public in the U.S. files documents with the SEC. With some minor limitations, it can withdraw from the process at any time. Understandably, media focus is on IPO successes rather than failures, although more than one in five filers does so. Withdrawal is not always a bad thing. For some firms a better offer arrives (e.g., a buyout bid) while for others it is a bad thing (e.g., investors are unwilling to invest). Importantly, the net result of a withdrawal is one less publicly traded competitor. In a recent paper I have with Dr. Craig Dunbar, we show that the existing publicly traded competitors experience a positive cumulative abnormal return of about .35% when a “would be” competitor fails to complete its IPO. Can you profit from this? Not likely. You would have to predict a withdrawal, and then buy stock in competing firms. Only those inside the firm’s IPO process would have enough insight. The rest of us must read the tea leaves.

Monthly Archives: October 2015

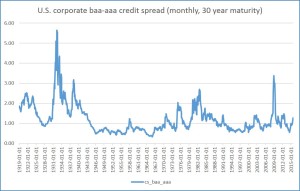

The graph shows the monthly U.S. corporate credit spread of Baa-rated bonds minus AAA-rated bonds. The bond yields are calculated as Moody’s seasoned corporate bond yields with maturities as close as possible to 30 years. Meaning? When the likelihood of default increases, the bond yield increases. Baa firms are more likely to default than AAA firms. When good economic conditions are expected, investors expect both Baa and AAA firms not to default, and thus the credit spread is small. When poor economic conditions are expected, the likelihood of default of all firms increases, more so for Baa firms. As such, investors demand greater return (yield) and so we see the credit spread increase. A high spread generally indicates(expected) poor economic conditions.

A data file is here.